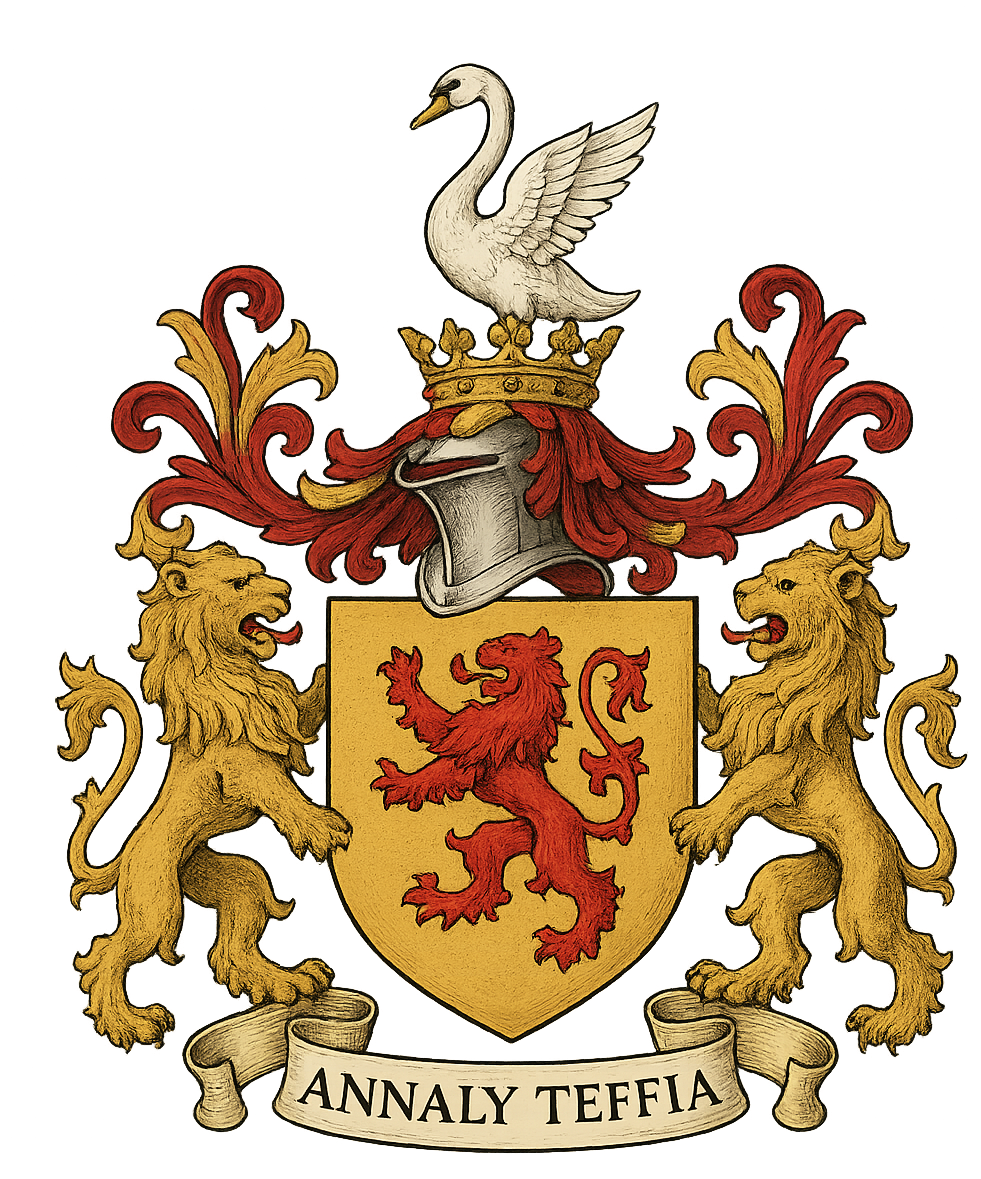

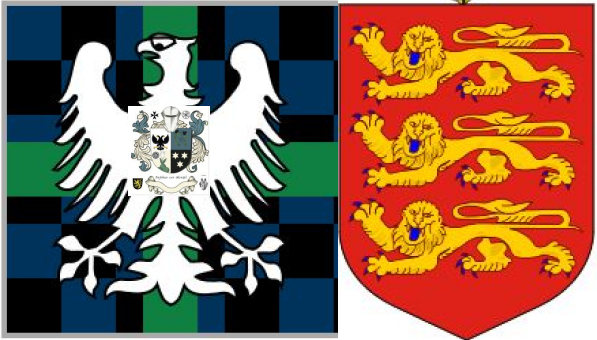

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

How England's Top Peerage Books recognized Annaly PrincesBelow is a careful, historically grounded explanation of how Burke’s and Debrett’s gave recognition to the principality-character of Annaly (Teffia) over the last few centuries—not by proclaiming a modern principality, but by how they classified, described, and contextualized its rulers and territory. 1. How Burke’s Peerage recognized AnnalyBurke’s method was genealogical-historical, not constitutional. Recognition came through language, framing, and continuity, rather than formal legal declarations. a) Princely terminology for the early rulersAcross multiple editions, Burke:

This is significant because Burke did not casually use “Prince” for Irish chiefs.

b) Territorial continuityBurke consistently treated:

That continuity is one of the hallmarks of principality-type recognition:

c) Treatment of the Delvin successionBurke presents the Barons (later Earls) of Delvin not as random conquerors, but as:

This framing preserves the idea that Annaly was translated, not extinguished. 2. How Debrett’s Peerage recognized AnnalyDebrett’s is more restrained, but that restraint actually strengthens its significance. a) Acceptance of princely originsDebrett’s:

Debrett’s avoids florid language—so when it preserves the term Prince or notes princely origin, it is doing so deliberately. b) Clear separation between origin and later peerageDebrett’s is very precise in showing:

That separation matters.

c) No repudiationEqually important: In peerage practice, silence can be as meaningful as affirmation.

It does none of those. 3. What this recognition was notNeither Burke’s nor Debrett’s ever claimed that:

Their recognition is historical and classificatory, not constitutional. That actually makes it stronger, not weaker. 4. Why this is unusualAcross Ireland and Britain:

Annaly is different because:

That combination is extremely rare. Bottom line (precise formulation)Over several centuries:

Together, they do exactly what peerage authorities are meant to do:

Here’s the clean, historically defensible way to explain how the Barons of Delvin and later Earls of Westmeath became successors to the princely realm of Annaly (Teffia)—not as conquerors who erased it, but as inheritors who translated it into feudal form. 1. Annaly was a territorial principality, not just a lordshipAnnaly (Teffia) existed first as:

That matters because succession in medieval law follows territory, not just bloodlines. 2. The English Crown’s policy: translation, not annihilationBy the later Middle Ages, the Crown had largely abandoned the idea of wiping out ancient Irish polities wholesale. Instead, it favored:

Annaly followed this model. 3. The Barons of Delvin as territorial successorsThe Nugent family—holding the title Baron Delvin—did not receive random parcels of land. They became:

This is succession by territorial assumption, a recognized medieval principle.

4. Why this is succession, not conquestSeveral factors show continuity:

In contrast, true conquest cases erase names, borders, and identity. 5. Elevation to the Earldom of WestmeathWhen the Delvin line was raised to the dignity of Earl of Westmeath, the elevation:

Earldoms are additive dignities. 6. Peerage treatment confirms successionEnglish peerage authorities consistently:

That silence is important. 7. The correct historical formulationThe most accurate phrasing—usable in a dossier or academic context—is:

That sentence reflects:

8. Why this is rareAlmost nowhere else do we see:

That combination is why Annaly stands apart. What happened in Annaly does not follow the normal English feudal pattern, and there are almost no true parallels. Let’s unpack why. 1. Princes — inside an English feudal “Honour”In most English (and Anglo-Irish) honours:

Annaly is different because:

👉 There are no other English feudal honours where:

That alone puts Annaly in a class of one. 2. Displacement by an indigenous successor, not a Norman conquerorHere is where Annaly becomes exceptional even by Irish standards. In almost every other case:

In Annaly:

This created a continuity of native territorial identity, even as governance changed. 3. Not conquest — but succession and translationAnnaly did not experience:

Instead, it experienced:

This is why:

That is almost unheard of in English feudal history. 4. Why this doesn’t exist elsewhereLet’s compare: Wales

Scotland

Continental Europe

Other Irish lordships

👉 Annaly stands alone in combining all four:

5. The correct historical classificationSo the most accurate way to describe Annaly is:

That sentence alone explains why:

Bottom lineYes — Annaly is one of the only, and arguably the only, English feudal honour where:

That combination is extraordinarily rare.

|

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Chronology of Teffia Annaly Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Nugents of Annaly Ireland Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News