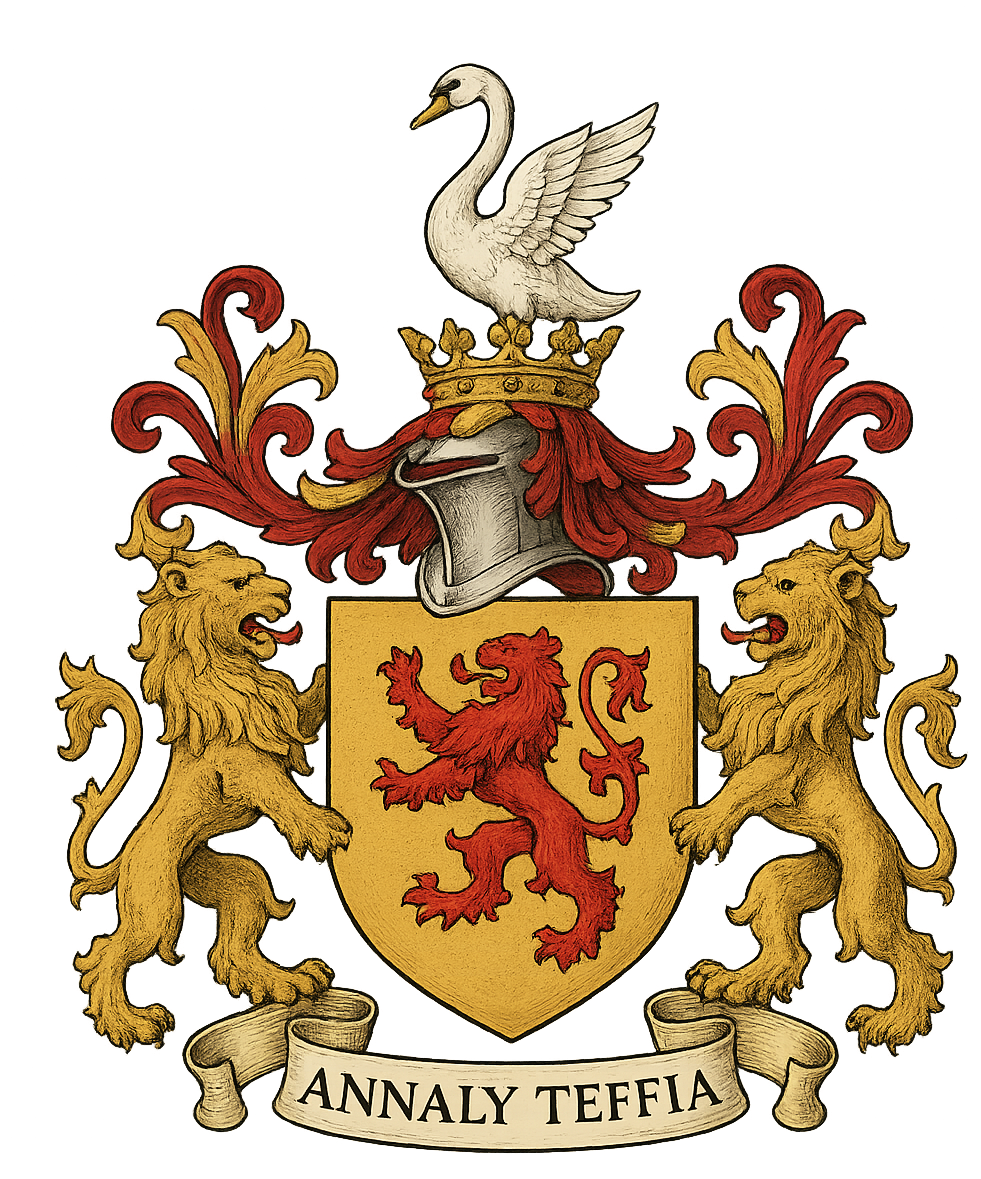

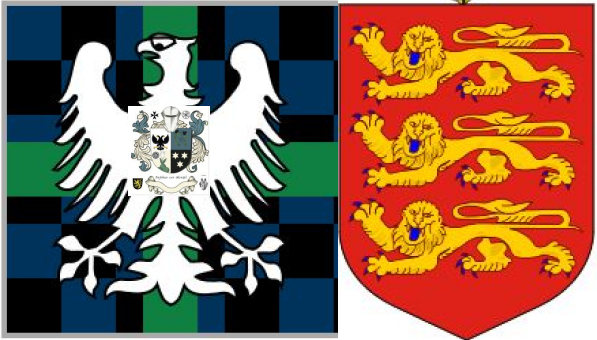

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

From Overlordship to Interregnum:How Ireland’s Indigenous Princes Passed Through a 740-Year Arc to a Moment of De Facto Sovereignty (1172–1937)What follows is a precise, date-anchored legal–historical explanation of how Ireland’s indigenous princely seignories—such as Annaly–Teffia (Longford)—moved from Crown-recognized principalities under English overlordship to a short but consequential interregnum in which English authority was displaced before a republican constitution formally re-ordered sovereignty. The argument does not claim a wholesale restoration of medieval kingship by statute; rather, it explains how recognized dignities were never expressly abolished, creating a legal anomaly during the revolutionary transition. I. Recognition and Conversion (1172–1605)1172 — Royal Recognition Begins

c. 1200–1300 — Palatine & Captaincy Governance

1541–1603 — Tudor Surrender and Regrant

1605 — Final Crown Instruments in the Region

II. Union Without Abolition (1605–1801)1605–1800 — Administration, Not Extinction

1801 — Act of Union

III. Displacement and the Legal Gap (1916–1937)1916 — Easter Rising

1921 — Anglo-Irish Treaty

1922 — Irish Free State

1937 — Bunreacht na hÉireann (Irish Constitution)

IV. The Governing Legal Principle (Applied)The situation may be stated with precision:

Why this matters in 1922–1937: V. What “Sovereigns of Their Seignories” Means (Carefully)

VI. ConclusionFrom 1172 to 1937, Ireland’s indigenous principalities passed through recognition, conversion, union, and finally displacement without abolition. The Irish Revolution created a legal anomaly: English governance ended, yet the feudal dignities England had recognized and converted were never expressly extinguished. Until the constitutional settlement of 1937, that gap left ancient princely seignories—such as Annaly–Teffia—legally unextinguished, with their representative dignity surviving as honours in gross in the successors of Delvin and Westmeath. Irish Princely Peerage Recognized in European Nobility Books and Guides.For centuries, English and European peerage literature consistently acknowledged the ancient princely character of Annaly and Teffia and other ancient Irish Gaelic Kingdoms, treating them as legitimate territorial dignities rather than mere local lordships. From early modern compilations onward, works such as Burke’s Peerage, The Complete Peerage, and continental Adelsbücher recorded the rulers of Annaly–Teffia as princes or chiefs of princely rank, often noting their status as ancient princes of Ireland or as holders of converted princely authority. These entries were not casual antiquarian flourishes; they reflected the English Crown’s long-standing recognition of Irish principalities and the legal–genealogical need to preserve precedence, descent, and dignity within the wider European nobiliary system. Importantly, peerage and Adels books functioned as repositories of noble legitimacy, not merely lists of sitting peers. They preserved titles that pre-dated English patents, including Irish princely dignities recognized through homage, treaty, and later feudal conversion. As a result, Annaly and Teffia appeared repeatedly across centuries of noble literature as recognized princely seignories, even after their governance was transformed under English law. The persistence of these references—well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—demonstrates that English and European nobiliary authorities understood Annaly–Teffia to possess a princely antiquity and dignity that survived political change, and which merited continued recognition in the formal record of Europe’s noble houses. English and European nobiliary works—most notably Burke’s Peerage and related continental Adelsbücher—long recognized a range of Gaelic princes as holders of legitimate princely rank, recording them as ancient territorial rulers even when they were not English peers of Parliament. Among those repeatedly acknowledged were the O’Neills of Tyrone (styled Princes or Kings of Ulster), the O’Briens of Thomond (Princes of Thomond and descendants of Brian Boru), the MacCarthy Mórs of Desmond (chief princes of Munster), the O’Donnells of Tyrconnell (Princes of Tyrconnell), the O’Conor Don of Connacht (royal and princely rulers of Connacht), the O’Rourkes of Bréifne (Princes of Bréifne), and the O’Farrells of Annaly–Teffia (Princes of Annaly). Burke’s and similar authorities preserved these titles to establish antiquity, precedence, and lawful descent, reflecting the English Crown’s historical recognition of Irish principalities and the European practice of recording noble dignity by blood and territory, even after sovereignty was converted or displaced. As of 2025, a review of mainstream genealogical, peerage, and nobiliary literature reveals no active, competing claimants publicly asserting succession to the ancient 21 or so Ancient kingdoms or princely seignories of Annaly–Teffia in a manner recognized by English or European nobiliary convention. The historic Gaelic dynasties once associated with Annaly are long extinct in the male line or have not advanced documented, continuous claims to territorial princely dignity in modern peerage or Adelsbuch records. By contrast, the successors of the Earls of Westmeath, through the Honour of Longford (Annaly) created and maintained under English feudal conversion, remain the only line historically documented as holding representative authority over the former principality—first as captains of the country and later as feudal successors-in-representation. While modern Irish constitutional law does not adjudicate medieval dignities, within the framework of historical–legal analysis and nobiliary continuity, no parallel or rival claims to the Annaly–Teffia princely complex are presently evidenced, leaving the Westmeath succession as the sole continuously recorded line connected to that converted princely honour. |

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Chronology of Teffia Annaly Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Nugents of Annaly Ireland Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News