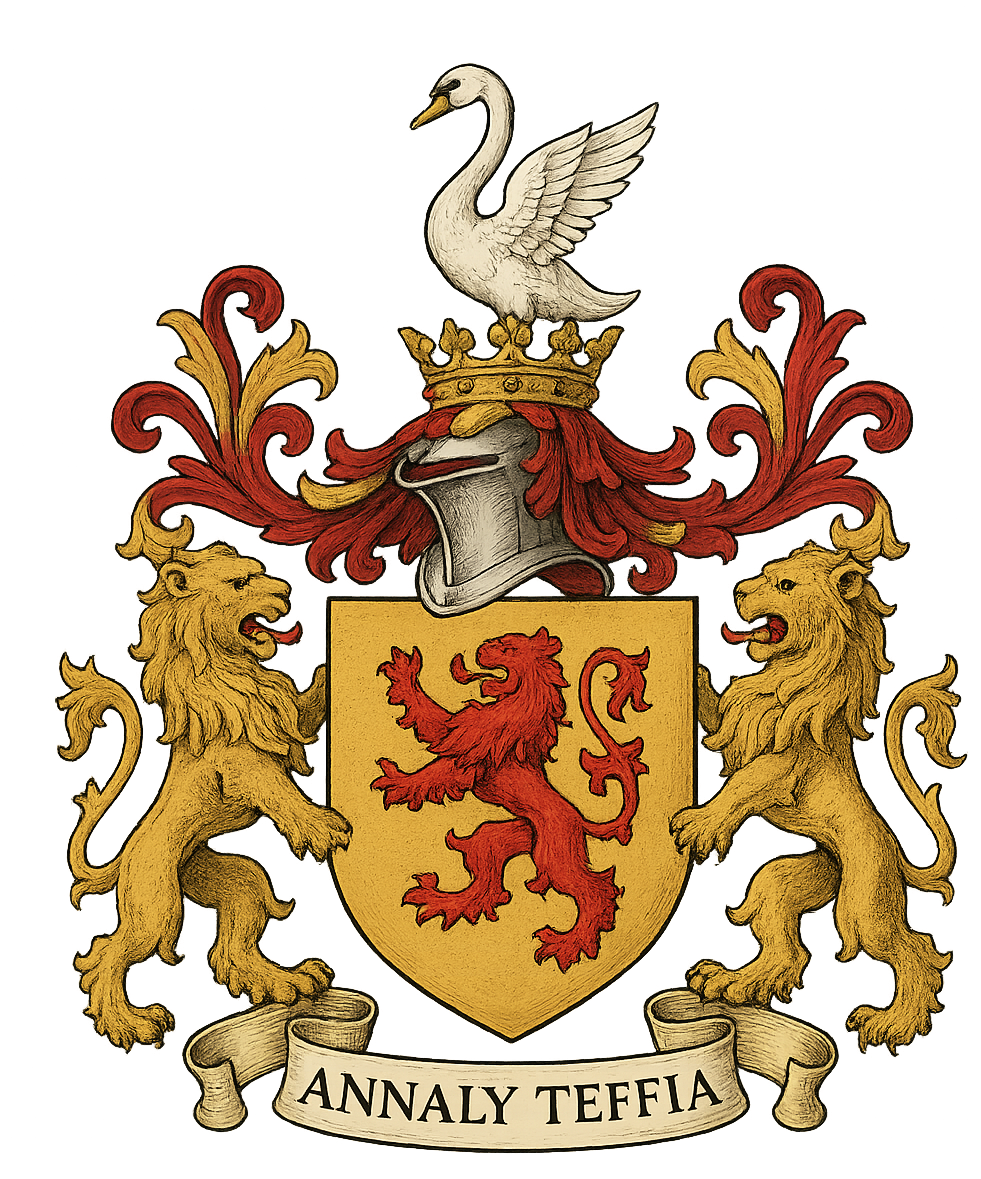

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

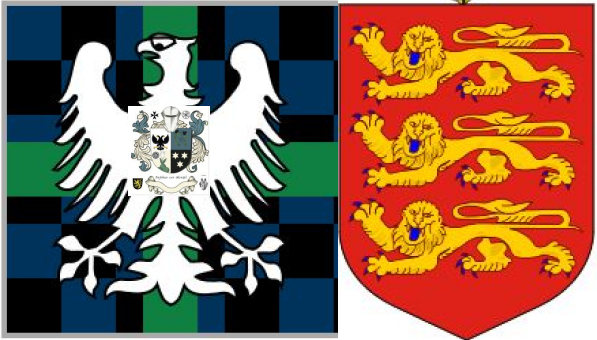

Blackstone’s “Commentaries on the Laws of England” (1768) applies to the Honour and Feudal Principality of Annaly and Longford, held by Dr./Jur. George Mentz, Seigneur of Fief Blondel — while preserving Blackstone’s original meaning and spirit. ⚜️ Commentary on the Feudal and Incorporeal Rights of the Honour of Annaly and LongfordAdapted from Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1768), Book II, Chapters II–III. Of Incorporeal Hereditaments within the Honour and Principality of Annaly–LongfordThe Honour and Seignory of Annaly and Longford, now held by George Mentz, Seigneur of Fief Blondel, represents a collection of incorporeal hereditaments—that is, hereditary rights and privileges issuing out of, or annexed to, lands and tenements within the ancient territories of Annaly, Westmeath, and Longford, formerly part of the Liberty of Meath. In legal contemplation, these incorporeal rights are intangible dignities, franchises, and liberties—not the soil or land itself, but

the honours, jurisdictions, and profits issuing therefrom. Nature of the HonourAn Honour (or Barony Palatine) such as Annaly and Longford consists of:

These rights are incorporeal hereditaments: unseen yet lawful and inheritable dignities derived from royal authority. Of Feudal and Palatine LibertiesUnder the ancient Liberty of Meath, the Nugents (Barons of Delvin, later Earls of Westmeath) and

their heirs exercised palatine powers across western Meath and Annaly—powers akin to those of a small sovereign.

In modern legal language, these are incorporeal but inheritable dignities—juridical powers attached to the seignory, not to any one manor or castle. Of Dignities and FranchisesThe Honour of Annaly and Longford comprises dignities and franchises, meaning royal privileges held by a subject.

These rights are treated in law as franchises subtracted from the Crown and vested perpetually in the grantee or his heirs. Of Rents and ServicesThe feudal nature of the Annaly–Longford Honour is evidenced by its rents and feudal

services. Of Common Rights, Fisheries, and ForestsThe Honour further embraces rights of common, pasture, turbary, and free fishery—all classical incorporeal

rights in the sense of Blackstone.

These rights, though invisible, are perpetual and inheritable components of the seignory, descending with the title of lordship. Hereditaments of a Dignity and Legal StatusIn English law, a dignity—such as a barony, honour, or palatine lordship—is itself an incorporeal hereditament of the highest order. It conveys precedence, feudal authority, and hereditary title, independent of landholding. Thus, the Honour and Principality of Annaly and Longford is not merely an estate, but a juridical sovereignty-in-miniature—a feudal dignity held in fee simple, originally granted from the Crown to the Nugent line and lawfully conveyed to Dr./Jur. George Mentz in the modern era. ⚖️ Summary

|

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Chronology of Teffia Annaly Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Nugents of Annaly Ireland Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News